I really enjoyed our Educational Psychology course this semester. There were a number of takeaways from the class, like Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, that I found interesting and it was great when I actually witnessed the theory in action while observing classes at Belmont Secondary.

I really enjoyed our Educational Psychology course this semester. There were a number of takeaways from the class, like Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, that I found interesting and it was great when I actually witnessed the theory in action while observing classes at Belmont Secondary.

I came across this article on the teenage brain and I think it makes some important observations for us educators, particularly in secondary education. Basically, the article details a number of studies done on the teenage brain relating to risk-taking, peer pressure and self-control. As we learned in Ed-Psyche, conventional wisdoms on teenage brains and learning have largely been debunked through advances in brain scanning technologies like MRI. The article looks at three studies done on adolescents and mice (not the most reliable for determining human brain function, admittedly); the first looking at the influence of peers on risk-taking behaviour.

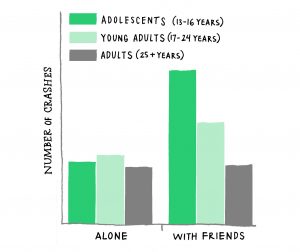

The first study involved having adolescents play a driving situation game in which they had to navigate a series of stoplights. When teens played alone, there was no difference in their performance in comparison to the adult control group. However, when their same-aged peers were allowed to observe the teens play, the adolescents were three times more likely to take risks resulting in crashes. The conclusion of the study was that “peer pressure emerges as a measurable biological phenomenon, crossing over into the perceptible world…”.

The first study involved having adolescents play a driving situation game in which they had to navigate a series of stoplights. When teens played alone, there was no difference in their performance in comparison to the adult control group. However, when their same-aged peers were allowed to observe the teens play, the adolescents were three times more likely to take risks resulting in crashes. The conclusion of the study was that “peer pressure emerges as a measurable biological phenomenon, crossing over into the perceptible world…”.

Ok, great, now we know that the old wisdom “teens do dumb stuff” is not only true, but we have a better idea of why. Also interesting in the article was the explanation of how teenage brains develop over time. Apparently the brain’s limbic system (our centre of primal instincts like fear, lust, and hunger) is fully developed by adolescence. However, the brains prefrontal cortex (responsible for self-control, planning, and self-awareness) is still busy developing. This would explain why adolescents are often aware of risky behaviour, but do it anyway. Interesting.

Well, the findings of the studies don’t exactly seem encouraging before heading into the classroom, but helpfully the author has three pieces of advice that I think are useful for when we enter the classroom.

- Take a direct approach: take the time to explain the brain’s development to students and how the limbic system, peer pressure, and risk-taking are all part of their current development. The reasoning for this is that if they understand themselves, they are more likely to recognize their impulses and know why.

- Make good use of peer pressure: use teen leaders, positive social role models and examples of social justice to change undesirable behaviour (bullying, vaping, etc.). As we’ve learned, adolescents will actively model behaviour that they see, and so providing them with positive examples is important.

- Teach self-regulation: teaching things like long-term planning, self-regulation, and empathy do benefit teenagers despite the fact that their brains are still developing. They will still be impulsive, but this awareness might help mitigate any problem behaviour.

Leave a Reply